The imminence of a Teaching Excellence Framework in the UK is placing our existing bundle of metrics under fresh scrutiny. Hence recent attention to employability, measured now by the Destination of Leavers from Higher Education (DLHE) survey, which tracks down graduates six months after they have received their degrees.

We’re all familiar with DLHE data: in the coming weeks I, like thousands of other academics across the country, will be quoting figures at open days. I’ve also been to plenty of meetings at which ‘employability strategy’ has been code for ‘getting the right graduates to complete DLHE’.

Johnny Rich, meanwhile, is the latest of a long line of critics to argue that DLHE is a poor proxy for a measure of employability. Rich’s timely report, Employability: Degrees of Value, argues that graduate employment is a very different thing from employability. Moreover, focus on the former, since it produces our familiar metric, can distract us from the more important labour required by the latter. This seems to me worth some thought.

- Employability & apple pie

So how should we define employability? Here are two existing efforts, taken from a Higher Education Academy report (p. 6):

- ‘A set of achievements – skills, understandings and personal attributes – that make individuals more likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen occupations, which benefits themselves, the workforce, the community and the economy.’ (Knight & Yorke, 2003)

- ‘The qualities, skills and understandings a university community agrees its students would desirably develop during their time at the institution and, consequently, shape the contribution they are able to make to their profession and as a citizen.’ (Bowden, et al., 2000)

And then there’s Rich’s definition, boiled down into three terms: ‘knowledge, skills and social capital’.

There’s a degree of commonality across these definitions, and a degree of beauty to them as well. Thinking about employability, they teach us, is thinking about helping students get where they want to go. And Rich, in particular, is very good on ‘soft skills’, powerfully shifting the focus away from those skills that appear to lead directly to jobs, and onto ‘the transferable skills that employers say time and again that they want’.

But there’s also a degree of fuzziness. The notion of ‘employability’ risks collapsing into ‘all that’s kind of good about education’. Indeed for Rich ‘employability’ is roughly equivalent to ‘learning gain’: another notoriously woolly concept. So this is great – honestly, it is – but it doesn’t necessarily help when I’m trying to convince sceptical parents that an English degree is the right way forward for Sophie. Nor does it necessarily help me identify concrete steps forward in improving ‘employability’ within my department.

- ‘What do you want to do when you grow up?’

Anyone who has been a personal tutor has experienced excruciating ‘what do you want to do when you leave?’ discussions. Actually, I think they serve a purpose, if only to remind students that we actually care. But regardless of whether the student has any ideas: what the hell do we know? Academics are not careers advisors, and tend to be united by our limited range of life experience.

A focus on (soft) skills, however, opens avenues for more creative interactions. One outstanding example, cited by Rich, is Durham’s ‘Skills to Succeed’ initiative. While many universities, including my own, have tried skills audits in different forms, this looks notably sophisticated, guiding students sensibly through the rationale for the process. And the real genius is the timing. Durham’s students complete the audit before they arrive. Surely this is precisely the right transitional moment for them to reflect upon where they are, and what they want to achieve at university.

- ‘No jobs in the humanities’

We’re all well aware of an instrumentalist discourse that positions the humanities as hopelessly impractical, an unaffordable luxury in an age of austerity. Actually this is much more prevalent in the US and parts of Asia than in the UK, but never too far away.

In this context, Rich’s table of soft skills (right) is a blessing, since it speaks so

directly to much of what we do in the humanities. Yet it also poses questions. Might we be doing more – or doing what we do differently – in order to stretch our students that little bit more?

I’m a big advocate of interdisciplinarity, and I like models (Durham again, also Warwick) which prioritize opportunities for students to step out of single-honours comfort-zones. University affords precious opportunities to develop new skills – languages, numeracy, entrepreneurship, and so forth – and too often our structures mitigate against them. Likewise, interdisciplinary programmes, intelligently designed, can directly address Rich’s list. ‘Liberal arts’ can mean a range of different things in the UK, but at its best it signifies a calculated interdisciplinary stretch.

And there are also lessons for the ways we teach and assess. Some careful thought addressing how to develop these soft skills might pull us in new directions: maybe away, in some programmes, from so many essays and exams; maybe also away from a reliance on lectures.

——–

But I can’t help feeling, for all that is obviously right about Rich’s arguments, that something is missing. Indeed I’ve read a lot of commentary on employability and graduate employment data recently, and I’m still waiting for someone to propose a realistic alternative to DLHE. And, thinking politically, we want something; we can’t ignore the value that DLHE’s figures – demonstrating as they do the value that degrees add – give the sector.

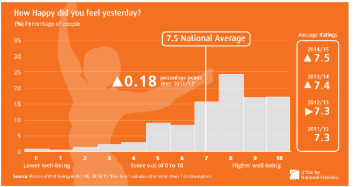

What else to measure? Presumably stretching the DLHE deadline from six months  after graduation to, say, 2-5 years, would produce richer data. Some of the best-equipped graduates, in terms of soft skills, take time to settle. Learning gain? They’re working on it. Maybe the best alternative of all, meanwhile, would be the ‘happiness index’, or national well-being data, that David Cameron endorsed in younger days. But, seriously, are we going to be able to justify more funding for English degrees on the grounds they make graduates happier? I’d love to think so …

after graduation to, say, 2-5 years, would produce richer data. Some of the best-equipped graduates, in terms of soft skills, take time to settle. Learning gain? They’re working on it. Maybe the best alternative of all, meanwhile, would be the ‘happiness index’, or national well-being data, that David Cameron endorsed in younger days. But, seriously, are we going to be able to justify more funding for English degrees on the grounds they make graduates happier? I’d love to think so …

[…] will also have the opportunity to add further optional questions. A year ago I facetiously suggested calibrating DLHE with a national happiness index; HEFCE has opted instead for […]

I’m very flattered by your kind and thoughtful response to my paper.

One of my intentions was to suggest an approach to measure employability better as well as support it better. As you suggest, that is not unrelated to the efforts to develop metrics of learning gain.

I wouldn’t recommend greater reliance on a longer term DLHE. There are still the same problems, albeit slightly ameliorated: it’s only a snapshot; it measures employment, not employability; etc. Also there is already a ‘long DLHE’ which is helpful (particularly in concert with the ‘short DLHE’), but which has practical problems. The more useful a survey is by being longer, the harder it is to gather data and the more the quality drops off.

I’m also not convinced by a happiness score. Apart from being notoriously difficult to measure in any meaningful way, happiness is perhaps too vague a goal to provide useful data to inform better policies or practice. The difficulties outweigh the potential benefits.

Having said that, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that we all want students to go on to lead happier, more fulfilled lives as active contributors to a happier, more prosperous and civilised society. Being employable is only a small part of that, albeit an important part.

Reblogged this on johnnysrich.